First published in Issue 120 of Copper Magazine

My Audio Journey, Part Two – PS Audio

Written by Adrian Wu

Copper reader Adrian Wu lives in Hong Kong and has spent time in the UK and elsewhere, as you will see. He is a contributor to the Asia Audio Society website, dedicated to reference-quality sound and reproduction. As you will also see, Adrian, like so many of us, has had quite an audio journey, which he is kind enough to share with us and which we will run in two parts, to be concluded in Issue 121.

I would like to say thank you to everyone involved in Copper. For me, this is the one true magazine for music and audio lovers, devoid of commercial interests and packed full of practical information, learned opinion and thought-provoking comments. Looking back at my audio journey of almost 40 years, I have made many friends and continue to learn new things every day that I will treasure for the rest of my life. And I get to use the stuff I learned in my physics and math classes at school!

I have been a music lover all my life. I started learning the piano at the age of eight, and I was very fortunate to encounter my second teacher after I started boarding school in the UK. He was a retired concert pianist with a mind-boggling repertoire, but he also taught me a lot about how to be a decent and honorable human being. From that day on, music became a major focus of my life.

My introduction into audio came after I joined the electronics club organized by my high school physics teacher. One day after our club session, he asked for volunteers to help him with a project in his home. My friend and I volunteered, and that was the first time I laid my eyes on the Quad ESL electrostatic loudspeaker (or any audiophile equipment for that matter). At the time, the ESL was still available new from the factory, but being a high school teacher, he could only afford a second hand pair. He wanted to upgrade the EHT power supply unit, and we helped him remove the covers. Not having allowed them enough time for their membranes to adequately discharge, he stuck his hand in and was promptly thrown back several feet onto his butt by the 6000 volts (thankfully of high source resistance) still lurking around. Having witnessed this debacle, I knew that instant that these were the speakers for me.

Quad advertisement from Audio, October 1959.

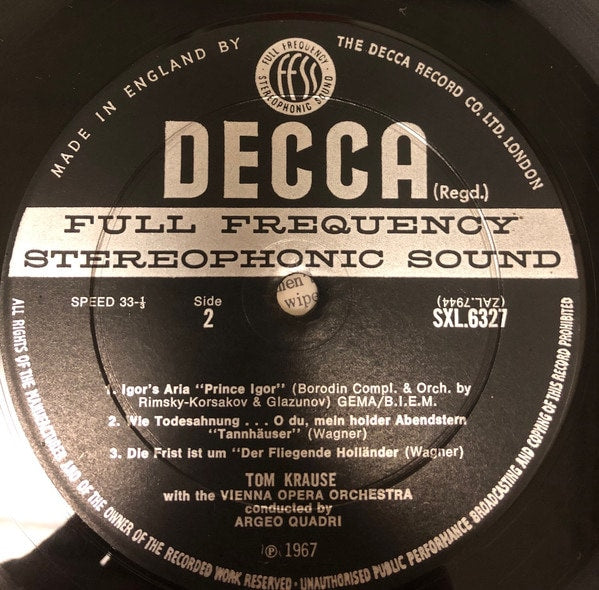

During my university years living in Edinburgh, I eagerly awaited every new issue of Hi-Fi News & Record Review. I saved up my allowance (not having a girlfriend helped) and bought my first stereo, which was made up of the Dunlop Systemdek II turntable (aka the “pressure cooker”), Mission 774 arm (designer John Bicht’s classic) and Audio-Technica AT33 cartridge. Amplification was an Arcam integrated, driving KEF Coda 3 speakers. A Frenchman operated a used record store at his wine shop in New Town, and I bought the wide- and narrow-band Deccas (the wide band issues were the early premium releases, including the whole SXL2000 series, and the early SXL6000 series from 1962 until 1970. These were mostly produced with tube electronics. The later SXL6000 narrow band issues were all produced with solid state electronics), EMI ASDs and SAXs, French Pathé Marconis and Lyritas etc. that nobody wanted because the CD offered perfect sound forever. As the Scots were frugal and took great care of their possessions, the LPs I bought were mostly pristine. These still make up the core of my record collection. I investigated CD audio, and decided it was not for me. CDs cost 10 pounds in those days, whereas I could pick up a mint second hand Decca LP for about 2 pounds.

“Narrow band” Decca label.

“Wide band” Decca label.

My classmate Neil was a Linn evangelist. After he saved up enough money, we went to the Linn dealer in Edinburgh to audition the Linn Sondek LP12 turntable. The salesman (barely out of high school) was shocked that someone wanted to actually listen to the thing. What was the point of auditioning since the product’s superiority was cast in stone? He took one out of storage, got it out of the box, plonked it on top of the box, hooked it up and put on a record. It might have been Steely Dan’s Gaucho if I remember correctly.

The record player had an Ittok arm and a Karma cartridge, top level in those days, but we could see the suspension bouncing in every direction except vertically. The cartridge mistracked every few revolutions and the sound was awful. After a few minutes, my friend leapt up from his seat and exclaimed, “That’s wonderful. I want one now.” And he parted with his cash, hard-earned during years of summer jobs (and no girlfriend), just like that. Talk about Ivor worshipping! The next time I visited Neil, he proudly played his copy of Gaucho through his officially approved system consisting of the LP12 with Naim Nait electronics and Linn Kan loudspeakers.

I credit Mr. Winston Ma (better known outside Hong Kong as the founder of the record label First Impression Music) for my early education in all things audio. During my holidays when I would go back to Hong Kong, I loved to hang around his shop, Golden String, in the Central business district. He was already very well-known and well-respected within the industry in those days, but he and his staff would spend hours explaining things to me, someone who couldn’t even afford the cheapest merchandise in his shop. He was the agent for brands such as Cabasse, Burmester and Koetsu, not exactly equipment that a university student could aspire to buying.

One day, a customer walked into the shop in the middle of the afternoon. He was dressed in the type of clothes worn by men who pulled rickshaws and by dock laborers, and he was wearing dirty old canvas shoes (way before those became fashionable). He did not know who Mr. Ma was, but nevertheless, Mr. Ma greeted him warmly and spent a lot of time introducing him to various products. At the end, he pulled out a pile of cash from his pocket and bought a top Koetsu cartridge. I was totally amazed and said so to Mr. Ma. I will always remember his response. “To be successful in selling hi-fi is no different from what you need to do to be successful in life,” he said, “and that is to treat everyone as equal and with respect, no matter if you think they are rich or poor, smart or dumb, well or poorly educated.” This advice has served me well.

A current Koetsu Rosewood Signature Platinum cartridge.

Many years later, after he had emigrated to Seattle, we worked together on a project to release a series of recordings I had made for a Chinese violin prodigy (and that is another long story). Unfortunately, this project did not come to fruition due to his illness and untimely demise. I still go past that building from time to time, and the large window on the first floor is still the same after 35 years, only without the large Golden String logo. It still brings back fond memories.

After graduation and actually living off the fruits of my own labor, I saved enough money to buy an “antique” Bösendorfer (1928, to be exact) piano. A few years later, I sold my original system to a friend (who had been coveting it for some time), and upgraded to a Roksan Xerxes turntable with Artemis arm, Mission Cyrus integrated amplifier and Linn Tukan speakers. A chance encounter led me to move to the US for postgraduate training. I arrived with just a suitcase and rented a studio apartment, the only criteria being that it was large enough to accommodate my piano.

I bought a futon that folded into a sofa, which was the extent of my furniture. Fortunately, my piano arrived soon afterwards, having been sent away ahead of time for an overhaul, and then directly from the workshop to my new address. It also became my writing desk and dining table for the next year.

I was afflicted by the common audiophile malady of upgrade-itis, and soon ditched the Cyrus (since it had no option for 110 volts and needed a transformer to operate in the US) for a used conrad-johnson PV10a preamplifier (tubes!) and Aragon 4004 power amp. I didn’t go for a tube power amp after considering the potential maintenance cost. Being in an extremely busy job with a brutal call schedule meant not much time for music, but I did manage to start taking weekly piano lessons from a professor at The University of California, San Diego (and falling asleep during the lessons). She (in fact, her husband) had extremely impressive wall to wall shelves loaded with LPs along the corridor and the living room.

Another six years went by, and after landing an academic job back in Hong Kong, I moved back after having been away for 19 years. I soon picked up old friendships and made new ones. An old family friend introduced me to someone who had been into music recording since he was at university in Los Angeles during the late 1970s. Having known noted recording engineer and producer Allen Sides for a long time, he had a nice collection of vintage microphones (being a top investment banker in Hong Kong helped) and recorders. We could therefore play with his Neumann U47, U67, M49, M50 and AKG C12 mics, and even a mint condition Telefunken ELA-M251.

My new friend also needed a few able bodies who were willing to help him haul around tons of equipment. Together with another friend (a real estate guy) who had set up a mastering studio to keep himself amused, we managed to get a contract (pro-bono) with the Hong Kong Philharmonic to record some of their dress rehearsals and concerts for their archives. (Their employment contracts with musicians in those days excluded permission to make commercial recordings.)

We would set up the microphones early in the morning (usually on a weekend) for the afternoon rehearsal, and then the evening concert. We usually limited ourselves to eight microphones (to lighten somewhat the back-breaking labor), arranged in a “Decca tree” configuration behind the conductor, with two flanking mics and a few spot mics for the percussion, basses and wind instruments depending on the program. At my friend’s urging, I found a Nagra IV-S stereo analog recorder with a QGB 10.5-inch reel adapter in a BBC sale in London for 2,000 pounds. Another 800 francs for new heads and a once-over at Nagra, and it was good to go. I was also offered a Telefunken M21 tape recorder for 800 Euros, which I turned down due to a lack of space. They were throwing these out of radio stations in Europe to replace with DAT machines in those days. Apparently, the same stations were buying them back a few years later when they realized that some of the DAT recordings were having dropouts and becoming completely useless. I would have bought a Studer A820 deck if I had space; they didn’t go for that much in those days! We would feed the mics into a Studer analogue mixer, and the stereo out into a splitter to feed our two Nagras, and line level outputs from the mixer would be fed to a digital multitrack recorder for use by our real estate friend. For monitoring, we used active Tannoy loudspeakers.

Nagra IV-S recorder.

All that ended when the now-current director of the orchestra came in and did not want to continue with the arrangement, but it was fun when it lasted. At least, we got almost all the Mahler symphonies on tape (but not the 8th, sadly).

Back on the hi-fi front – the subchassis of my Roksan turntable warped after less than a year spent in Hong Kong. Apparently, this was a common problem in humid climates. Therefore, off I went to buy a new turntable from Excel Hi-Fi (now defunct), the biggest dealer (at the time) in Hong Kong. I decided to buy a Michell Orbe turntable with a Graham 2.2 arm and Lyra Helikon cartridge. The salesman was an industry veteran whom pretty much every audiophile in Hong Kong knew. When I enquired if he was going to set up the player for me, he sneered and said, “if you can’t set up a turntable yourself, you shouldn’t be in this hobby!” Having had 15 years of experience with turntables by then (and still having reasonable eyesight), I could of course set up the rig, but I expected some service after having spent that much money (which was of course peanuts from his perspective). In any case, we became good friends nevertheless, even though I never bought anything else from the shop.

After some time I was able to buy a flat. I finally had a chance to indulge in my childhood dream – the Quad ESL! During a trip to visit my sister in Leicester, England, I came across an ad in the local newspaper for a pair of Quad ESL loudspeakers and Quad II amplifiers. I borrowed my sister’s car and drove to meet the seller at a council estate. The ESLs were in excellent cosmetic condition, and at a very low price (something like 200 pounds). The amps were a bit beaten up but the price was also low. I bought the whole lot and spent the next few days packing them up to ship back home.

After the gear arrived at my home, my old electronics skills came in handy. I went shopping for a soldering station, oscilloscope, multimeter and tools. My recording partner was a wellspring of information, having been introduced to the world of vintage audio by his friend, legendary audio publisher and manufacturer Jean Hiraga, and having a collection of vintage gear to rival his mic collection (Western Electric amps, tubes, drivers and transformers etc.). He came over and we checked out the speakers. The voltage was weak, and the panels had faded. I therefore had to order new EHT units and panels from One Thing Audio, and the two of us rebuilt the speakers over the Easter holidays. The hardest part was installing the panels, and having to remove uncountable numbers of splinters from my fingers afterwards.

The amps were in their original state, which means wax leaking out of the transformers and components with badly drifted values. When researching about restoring these pieces, I came across a local chat group that provided a lot of information. I made friends with the administrator Tim, another banker. He is a walking encyclopedia of vacuum tubes and vintage hi-fi, especially British products, since like me, he went to boarding school in the UK. He can recite all the structural variances of different vintages of most of the common audio tubes from Mullard, Telefunken, Amperex and so on. He is a great one to consult on the authenticity of NOS (New Old Stock) tubes. He and two partners own a vintage hi-fi shop called Vintage Sound, which is really an excuse for them to buy stuff. Tim had collected pretty much every make and vintage of the classic BBC LS3/5a studio monitor speaker over a couple of decades (another anomaly of British audiophiles of our vintage, thanks to Ken Kessler), including a pair of rare prototypes with screwed-in back panels, until thieves broke in and stole the whole collection one weekend. They didn’t steal anything else, not even the rare tubes in the display cabinets. I guess they were too busy trying to remove the haul without being caught. I had never seen my friend so distraught, and he spent the next few years going around the second hand shops in Hong Kong and Guangzhou trying to buy back whatever he could.

Jean Hiraga with Adrian’s friend Tim at Vintage Sound.

In his shop, I have experienced some of the weirdest and most wonderful things: Quad corner horn loudspeakers, Lowther back-loaded horns, the original Williamson amp with Partridge transformers as well as pretty much every amplifier ever made by Leak, Radford and Pye, and all the vintage Tannoy drivers (one of his partners’ nicknames is “Tannoy Silver”).

One of the friends in our group was a German named Dieter. Dieter started working at Siemens when he was still in high school (his mom worked in the vacuum tube division of AEG), and stayed with the company until his retirement as the general manager of its medical business in Hong Kong ten years ago. A properly trained electronics engineer (meaning he studied vacuum tubes and analogue electronics), he had kept a copy of any datasheet, manual and schematic that he had ever come across at work, filed away in the typical meticulous German manner. He could recite off the top of his head the specifications of many Siemens tubes and parts. He had an enviable collection of C3M, AD1, EL156, F2A11 and other rare tubes, as well as Sikatrop capacitors and other vintage parts, and introduced these to me via the lovely amplifiers he built in his spare time. Sadly, he left Hong Kong and went back to Hamburg after his retirement, rented a garage and started rebuilding vintage Mercedes sports cars.

Having been bitten by the vintage bug, I started to look into this side of audio. Those were the days when one could still find good stuff on eBay. Having restored the Quad II amplifiers, I then realized that contrary to popular belief, they were not the best mates for the ESL speakers. One listen to my friend’s Mark Levinson ML2s driving the ESL put that myth to rest. I went off hunting for deals, and managed to score a pair of Leak TL12.1 amplifiers and a pair of Brook 12A and Telefunken V69a amps over the next few years. I started researching into vintage components, such as antique carbon composition resistors and their modern equivalents (like Kiwame carbon film resistors and so on), antique oil capacitors (TCC Super Metalpacks) vs. modern ones (Jensen and Audio Note PIO or paper in oil caps), chassis wires and other components.

Telefunken V69a amplifier with new chrome face plate.

Looking at the construction of the three amps sort of tells you the very different approaches the manufacturers took in building the amps. The Leak is very neat, with all the components mounted on a tag board. That might mean an unnecessarily long signal path, but it makes working on the amps very easy. All the wiring is in looms, tucked into the corners. In fact, having worked on these amps, I can tell you that any deviation from the original wiring arrangement could result in extra noise.

Telefunken V69a interior. Note the original wirewound resistors and ceramic-encased Siemens Sikatrop capacitors. Extreme quality here.

The original TCC oil coupling caps that came with those amps were electrically leaky. They had rubber end caps, unlike their superior military grade “Super Metalpack” cousins. The rubber had all hardened after decades. I put in some industrial polypropylene and foil caps and replaced all the resistors, which had all drifted in value, with Kiwame carbon films, to make sure the amps worked before investing in more expensive caps. Everything measured correctly, and indeed the amps sounded fine. I then ordered some copper foil PIO caps from Jensen and put those in.

The difference was obvious and can be summed up this way: with the plastic caps, I was listening to Carol Kidd singing. With the PIO caps, Carol Kidd was singing to me. I could experience more emotion and nuances, the little inflections in tone, the little mannerisms. The Super Metalpacks sounded a little more laid back but again had that organic quality missing from the plastic caps.

Leak TL12.1 amplifier. Note the open mains transformer signifying an earlier generation model. The author is using the older black base GEC KT66 rather than the more common brown base.

One issue with vintage amps like these is the difficulty in getting the old (no longer legal by today’s standards) power connectors. No IEC sockets on these. Fortunately, an old wireless (radio) shop in Kowloon still had a stock of these now-illegal connectors in their warehouse, which they were happy to sell to me, as well as some octal plugs that have also become hard to find. They also had a stash of NOS vacuum tubes for TV sets (the audio tubes were long gone) that they still displayed on their shop window, but that probably nobody had bought for 40 years. The shop was packed top to bottom with parts, but the two ladies who ran the store always knew where everything was. After having been in business for more than 60 years, it sadly closed its doors about 10 years ago.

Leak TL12.1 interior. The author has substituted the original carbon composition resistors with Kiwame carbon film capacitors, the original TCC Metalpack coupling capacitors with the TCC Super Metalpack capacitors, and the cathode bypass electrolytic capacitors with Solen polypropylene film capacitors. The author is allergic to electrolytic caps, and would not allow any to contaminate his system.

In my quest for ever-better sound I had purchased a pair of vintage Brook 12A amplifiers – but they came with a story. These amps use 2A3 output tubes in push-pull configuration, and were supposed to be Paul Klipsch’s favorite to drive his Klipschorns. The seller told me that the amplifiers he was selling were defective, the reason for the low price. He had bought them in a non-functioning state and had hired a technician to restore them. However, they sounded distorted even after restoration.

The Brook 12A amplifier.

The original wiring of the Brook was a rat’s nest, unlike the British and German amps I had encountered. After I received the amps, I confirmed that the sound was indeed distorted. I downloaded the schematic and checked the wiring. Everything appeared to be in order. I studied the schematic carefully and noticed that the polarity of one bypass cap was reversed. The cathodes of the 2A3s are directly connected to ground via the heater transformers, which means the control grids are at negative potential. The cap that bypasses the grids to ground should therefore have the positive terminal connected to ground, instead of the negative terminal as shown on the schematic. The technician must have used the same schematic (there was only one schematic on line as far as I could find), and made the same mistake. It would have been fine if he had used non-polar electrolytics. After reversing the polarity of the capacitors, the amps sounded like magic. I wrote to the seller to give him the news, and he was not pleased!

The next question was, which components should be used to restore the Brook? I tried Jupiter wax capacitors (the original version), which was a mistake, as they didn’t do well with the heat generated by the amplifiers. There was a temptation to use American components of the same vintage as the amps, such as the Sprague Black Beauties, but I worry about the reliability of these ancient components. I ended up putting in antique Siemens paper caps, since I had the right values on hand. For resistors, I used my favorite Kiwame carbon films. These retain the tone of the carbon composition resistors while maintaining stability, and they don’t burst into flame either. For chassis wire, I removed the cheap wire the technician put in, and used new production cotton-sheathed copper wire to maintain the antique look.

Interior of the Brook 12A amplifier, showing the Siemens coupling capacitors.

The pair of Telefunken V69 amplifiers I also bought around this time period actually came as a V69 and a V69a. The difference being that the older V69 has EF12 metal pentodes at the front, and the V69a has EF804S (glass) tubes. Coincidentally, my recording partner had a mismatched pair of V69/V69a amps as well. We therefore did a swap, and he kept the V69s, while I kept the V69as. The amps I bought had been sitting in a basement somewhere in Germany for 40 years. The metal had rusted, but with a bit of elbow grease, the layer of rust was removed from the very sturdy steel cage. The amp is a beautiful example of German quality and precision. Paper capacitors were used throughout, with not a single electrolytic to be found. All the resistors (wirewound) had retained their original values. All the caps were encased in ceramic, and therefore should last forever. I went through and checked everything several times, and decided to bite the bullet and just turn them on to see if they worked. I did not even use a Variac (to gradually bring them up to operating voltage, which is recommended when powering up vintage gear); I just plugged them in and flicked the switches. No bang, no smoke, even the indicator lights worked. I adjusted the tube bias and played some music. There was no noise, but there was some distortion. However, it was amazing that these amps with their original tubes were stored in a dank basement for 40 years and still worked almost perfectly without restoration.

Telefunken V69a amplifier with new chrome faceplate.

The frequency response of the amps was way off. It turned out that the insulation of the input transformers has broken down after all those years. Teflon wasn’t available for transformers in those days, and they used paper insulation. The dampness in the basement had destroyed the insulation. I contacted Telefunken USA and they were very kind to agree to rewind the transformers for me using the original specifications, but with Teflon insulation. The measured performance of the amps went back to the original spec with the restored input trannies.

The amps came with the standard battleship gray faceplates of all the Telefunken studio gear of the time. I had the plates replicated but with a chrome finish, which looked more in place in a domestic setting.

I have compared the three vintage amps I own for driving my restored Quad ESL electrostatic loudspeakers and a pair of Tannoy SRM10B studio monitors. The Leak TL12.1 has a lovely midrange; the bass is a bit soft, but it sounds very engaging and musical. The Brook 12A has a more detailed sound, with more clarity and transparency, especially in the upper registers. It is really lovely for strings and vocal. As for the Telefunken V69a, these amps use pentode output tubes, whereas the Leak has triode-connected KT66 and the Brook has directly-heated triodes. The V69a have better bass, with more impact and a more solid foundation. Music takes on a larger scale. This amp is also very detailed and transparent, but sounds a bit lean when compared to the Leak. I feel they are tonally more neutral though. I would prefer the V69a for rock and large scale orchestral music, the Brook for chamber music and female vocalists, and the Leak if a warmer sound is desired.

Going back to my day to day system: after moving back to Hong Kong from the US, the conrad-johnson PV10a preamp and Aragon amplifier now needed step-up transformers. Having upgraded my front end with a Michell Orbe turntable, Graham 2.2 arm and Lyra Helikon cartridge, I wanted to improve the other parts of the system as well.

Michell Orbe turntable.

I first met Tim de Paravicini at the Heathrow Penta Hi Fi show in the mid-1980s. He demonstrated his amplifiers with a Revox reel to reel tape player and stacked Quad ESLs, which was certainly unusual at the time and hard to forget. I’d kept in touch with him from time to time, and had always wanted to own his designs. During a trip to London, I went to Walrus Systems in London (now closed) and auditioned some of the EAR amplifiers. I ended up buying the 834P phono stage and the V12 integrated amplifier. The V12 was interesting as it used parallel push-pull ECC83 small-signal tubes for output! The current incarnation uses EL84s, and I have not heard it, but the original version had a rather distinct sonic signature. They actually worked rather well with the ESL, giving a very transparent, involving presentation.

As I got more into vintage audio, I found out that I could buy non-functioning or poorly functioning audio components, restore them to original specifications, and sell them for profit. Since I have more fun restoring and optimizing them than keeping them, this was a good way to sustain the hobby without the headache of finding somewhere to store the equipment. Hong Kong has a very vibrant audio scene and it is very easy to sell vintage and good-quality audio gear. For popular items, I could usually sell them within a day of placing an ad on the popular Review33 website. I was able to source equipment through classified ads abroad and this allowed me to gain knowledge through experimentation to find the best components for restoration.

I also got to know various local artisans such as transformer makers that few people knew existed. Various Leak and Pye amplifiers came and went, and my hobby was financially self-sustaining. I also started to look into turntables, specifically Garrards. My first 301 came about after I spied a Schedule 2 machine on a slate plinth (made by the now defunct Slate Audio) with an SME 3012/II arm and Clearaudio cartridge at a second hand shop in London for the grand price of 1000 pounds. The turntable had already been serviced and the whole thing was plug and play. I sold the cartridge and mounted my Lyra Helikon. It had the drive and the solidity that I felt was lacking in the Orbe. The music had more presence due to the improved dynamics. I decided this one was a keeper and sold the Orbe instead. I subsequently upgraded to a late grease-bearing model, selling the Schedule 2 to a Japanese enthusiast for a good price. As for the SME, as it had a plastic knife-edge bearing, it was a good excuse to upgrade to a bronze knife, and I rewired the arm with silver wire and added a bronze base for good measure. I stayed with this table for 15 years, only recently exchanging some of its parts for a Classic Turntable Company 301. The superior main bearing, sturdier chassis and perfectly balanced platter brought a huge improvement. The improved speed stability results in better dynamics and tonal stability, the lower noise floor manifests as better transparency, and the frequency response also became more extended. This turntable is probably the greatest bargain on the market, especially when compared to the reissue 301 from SME.

The SME reissue of the legendary Garrard 301 turntable.

I left academia after six years, having experienced the SARS epidemic while working at a public hospital. It was an experience I thought at the time I would never see again, but how wrong was I! I was also totally fed up with the politics of academia. After a few years, with the kids getting older, I thought it would be a good idea to move to a larger apartment closer to work. It was a perfect excuse to realize my long-planned project: horn loudspeakers.

As the apartment needed to be gutted and totally renovated, I engaged a friend who was an acoustical architect to design the lounge (my wife is an architect, but she was very tolerant!). This friend worked for a number of years at the Arup Group in the UK and was responsible for the design of a number of concert halls and performance venues before returning to Hong Kong to set up his design firm. He also advised the late Mr. Winston Ma (former owner of First Impression Music) during the construction of his listening room near Seattle in the late 1990s. I got to know my friend when I wanted to use a concert hall he designed for a recording session. The hall quickly gained a reputation as having the best acoustics in the territory.

After the first site visit of the new apartment, he liked what he saw, since the room was irregular, and had no parallel walls but had the correct dimensions. He designed the air conditioning system, a subject of great importance to me as AC noise has always been a problem in many recording venues, so much so that we try to avoid doing recordings in the summer. Four-inch acoustical foam was placed strategically inside the walls and the ceiling. He also designed a ceiling to break up the standing waves, a design that sent my wife into a tizzy, and which the contractor declared was impossible to build. We ended up with a compromise, a ceiling that slopes at different angles in four directions. It actually does not look so weird once we got used to it, but it always elicits some reaction from new visitors. He even designed the LP shelves on one wall to control the first reflections from the loudspeakers, with the records stored at a precise angle of 23 degrees.

The built in bass trap doubles as a storage unit (or is it the other way around?). The idea was to make it a normal living room with only subtle hints of acoustical treatment. When I check the RTA (real time analysis, a measurement of the frequency spectrum of an audio signal) from time to time, I am still amazed at the smoothness of the frequency response. And the AC is completely silent. Most importantly, being in an apartment, the room is soundproofed with a subfloor floating on rubber insulation (to isolate it from the walls, which transmit noise to other floors of the building), and the same type of doors that are used in recording studios were installed for the front entrance and the corridor leading to the bedrooms.

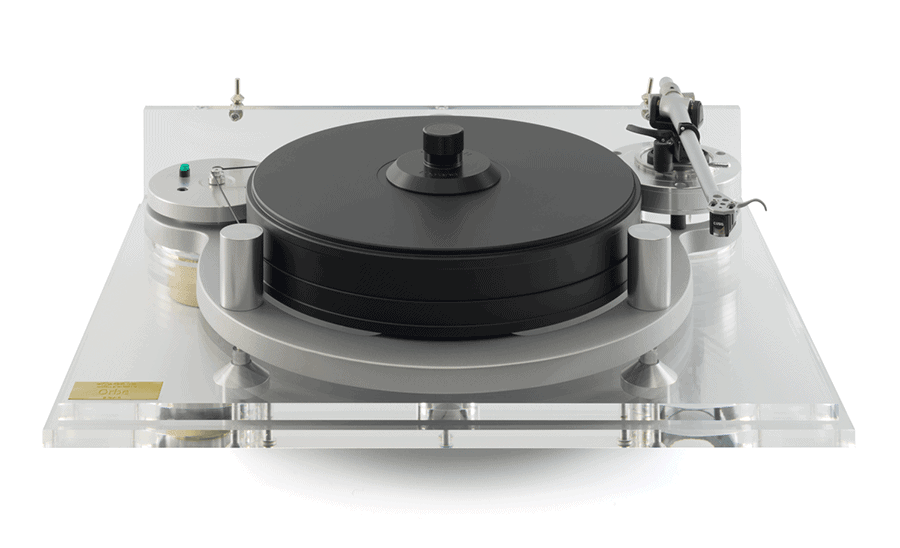

In the meantime, a pair of new horn speakers were planned. I had heard various horn iterations over the years in friends’ systems. Trips to Tokyo also presented opportunities to visit horn builders as well as antique audio dealers. I visited Jean Hiraga in Paris while he was still the editor of the magazine La Nouvelle Revue Du Son. He had set up at the time a pair of Altec A5 Voice of the Theatre loudspeakers, with his own crossovers, driven by Hafler solid state amps (no 300Bs!). The source was the original Philips CD player (probably modified, but my French at the time was not good enough to ask for details). Not exactly how I imagined it would be given his reputation. However, the sound was quite a revelation. Very dynamic, life-like and musical. He gave me a tube data manual (in French) as a gift. I also visited La Maison de L’Audiophile during that trip. Jean subsequently visited Hong Kong and gave me advice while I was setting up my horn system.

Altec A5 loudspeakers, “The Voice of the Theatre.”

During a trip to LA, I visited Dr. Bruce Edgar, creator of Edgarhorn loudspeakers. He was a very kind man and full of knowledge and experience. Unfortunately, he was in poor health at the time, having just got out of hospital after a leg infection, but he still spent an afternoon with me. I finally settled on the combination of an EV (ElectroVoice) T350 tweeter, a JBL2450 midrange (picked up at a good price in Hollywood) and Altec 515C bass drivers. I had trouble finding a good pair of vintage 515C. I then found out that an outfit called Great Plains Audio was servicing Altec drivers, and they had just started to produce some new drivers. I called the owner and explained to him what I wanted, but he was a bit bemused to learn that I wanted the Alnico version. He could not understand why since he did not believe it was in any way better than the ferrite version, and it loses magnetism over time. Anyway, I convinced him that there was a market for it, and he agreed finally to produce a prototype. Months passed, and he finally contacted me, telling me that he had a pair of prototypes that performed to the original spec. I bought them, and the 515C has been a regular item on his catalogue ever since.

I had considered various high-frequency drivers such as the JBL 077 and various Fostex models, but I had been impressed with the sound of the EV T350 at a friend’s place. Pretty much the only thing that can go wrong with these drivers is the voice coil, and amazingly, EV still produces these phenolic diaphragms. I bought a pair of 400 Hz rectangular exponential horns and reflex bass cabinets from a builder (Tatematu Onko, no longer in business) in Japan, the latter designed specifically for the 515C. I decided to use active crossovers, which allows for easy adjustments, maximizes sensitivity of the speakers and avoids adding reactance. I built a three-way crossover from Marchand Electronics initially, and subsequently switched to an Accuphase F-25 analogue frequency divider.

To backtrack a bit, a few years before I started the horn project, I got to know Allen Wright. In my quest to learn more about amplifier circuits, I came across his writing on the internet. Allen was an Australian guru who started his career as a technician at Tektronix. He designed the amplifier used in oscilloscopes, which were all tube-based in those days. These amplifiers needed to be extremely quiet and linear up to the megahertz range. He then decided to tackle audio and set up his own company, Vacuum State Electronics. He was very well respected within the DIY circle, and was in high demand for doing modifications and upgrades, as well as consulting for manufacturers.

He was developing his Realtime Preamplifier at the time, and wanted beta testers to iron out problems. I became one of his 10 beta testers, and was sent the components and the chassis to build the preamp. The design is very complicated, with a phono section that has an input sensitivity of 0.1mV. It is a dual mono, balanced differential design based on the E88CC tube. It has a shunt regulated power supply. Allen had a set of principles that he steadfastly adhered to. These included:

- A fully differential circuit.

- Zero negative feedback.

- Internal wiring with the thinnest conductors (solid wire and foil), preferably in pure silver

- He advocated using the cheapest RCA plugs and sockets (the conductors in audiophile connectors are too thick), or preferably, the Lemo Redel connectors (non-magnetic connectors normally used in MRI scanners and the defense industry).

- Teflon dielectric.

- All electrical “anchor points” are tightly regulated, which means the extensive use of current sinks and current sources to achieve the highest impedance possible.

- Choke-filtered power supply with solid state rectification. Fast-recovery diodes for high voltages, Schottky diodes for low voltages.

Vacuum State Electronics Realtime RTP3D preamplifier.

The whole experience was an excellent learning exercise, not only in the theory of audio electronics, but also in the art of point-to-point wiring construction. It took a good two years to finalize the prototype. The preamp is very quiet, dynamic and tonally neutral. I used it as my phono preamp for several years before buying a factory built RTP-3D version. Last year, I modified the prototype to serve as my tape head preamplifier.

For power amplification, I am using two pairs of Allen’s DPA300B tube amps. These amps have a differential input stage using a pair of the Russian 6H30Pi in cascode to drive a pair of 300B power tubes in push-pull configuration. These amps serve the tweeters and mid-range drivers, while a Mark Levinson No. 27.5 amplifier drives the bass.

Back to the loudspeaker discussion: a few years ago, I was introduced to a friend who had built a speaker system using field coil drivers made by G.I.P. Laboratory in Japan. These are recreations of the ancient Western Electric drivers, and are extremely expensive. The system had very impressive dynamics, but he was still working on integrating the various drivers, and the system was not very coherent as a whole. However, what it did do well got me interested in field coils. [A field coil loudspeaker uses an electromagnet which needs to be powered by DC, as opposed to more conventional speakers that use permanent magnets. – Ed.] The GIP drivers were out of my price range, but Line Magnetic in China also produces similar drivers at a somewhat lower price level.

However, I don’t believe 80 years of advances in science and engineering could not improve upon these ancient designs. Classic Audio Loudspeakers in Brighton, Michigan produces a line of modern field coil drivers using state of the art materials such as beryllium diaphragms, and the designs are based on Altec and JBL drivers. This meant I could get drop-in replacements to use in my current set up with minimal adjustments required. After detailed discussion with John Wolff, the designer of these drivers, I bought a pair of 6475, which is based on the JBL475, the consumer version of the 2450, and a pair of 1501, based on the Altec 515.

Classic Audio Loudspeakers 6475 driver.

The higher breakup frequency of the beryllium diaphragms allows me to operate the midrange drivers up to a higher frequency, and I moved the crossover frequency up an octave to 7kHz. There was an immediate and marked improvement with the new drivers. There is more detail and the dynamics, both at the micro and macro level, are greatly improved. The bass notes are faster and more tuneful. One can perceive the vibrations of the membrane of the tympani after each strike of the mallet. The tonal color of the instruments seems more natural and real.

I also changed from the T350s to the Acapella ion tweeters, something I had been very interested in doing ever since I heard them several years before. These tweeters use high-energy electrical plasma to vary air pressure and create sound. What I liked about the T350 is that the phenolic diaphragms avoid the hard edge that metal diaphragms can impart on the high frequencies. Yet the ion tweeters go further and impart a totally natural, ethereal quality to string tone, female voice and percussive instruments. The better high-frequency extension also gives an enhanced perception of space and depth. I estimate that the ion drivers made the greatest difference to my system, even though the frequency response of my ears rolls off above 12 kHz!

Acapella ion tweeter.

As I feel I have finally accomplished a satisfactory result with my speakers, I have moved on to deal with the recordings that I have made over the years. I needed a master recorder for editing and playback of the tapes. The Nagra IV-S is good for neither task; its playback electronics are more of an afterthought, and it does not allow for precise positioning of the tape for editing. The Nagra T-Audio recorder was initially developed as a scientific instrument, and later adapted for the television and film industry. Due to its substantial cost when it was introduced, it was too expensive for most music studios. The listed price in 1983 was £26,000, enough to buy a modest house in London!

Luckily, by the mid-2000s, analogue had fallen out of favor, and I was able to pick one up, fully refurbished with new heads, from Nagra for 8,000 CHF (about $8,800 US). I was attracted to its small footprint and the amazingly precise mechanical function, which makes tape editing very easy. However, the playback electronics of the machine, while competent, are not up to audiophile standard. The extensive use of 1980s-vintage op-amps and complicated compensation networks give the sound an unnatural, electronic character, although the dynamics and scale of the sound are outstanding.

Nagra T-Audio tape recorder.

There is now a trend for audiophiles to bypass the native electronics of professional recorders, and this was what I did. I wired the playback head with solid core pure silver wire directly to my prototype preamp, after modifying the RIAA EQ network for IEC and Nagramaster equalizations. (Most commercially available 15-ips tapes nowadays use IEC EQ, and all my own recordings use Nagramaster EQ.) It took some experimentation to optimize the frequency response, but the end result is highly satisfactory. The writeup about the modifications has been published at my group’s website (the Asia Audio Society) for those who are interested in the technical details. Tape playback avoids the pitfalls of LPs, such as distortion, noise and dynamic compression. It also sounds more natural and musical than the majority of digital recordings.

Commercial recordings are becoming available on 15-ips reel tapes from companies such as Tape Project, Analogue Productions and others. I also have a collection of master tape copies of some of my favorite music, which I have obtained from a couple of recording engineers in Europe.

I feel I have finally arrived at a sound that I find quite satisfactory, and I can just enjoy the music without worrying about what I need to do next (for a while).

However, I have been neglecting my turntable for quite a while! And I have not even started looking at digital…

Adrian Wu’s current system.