First published in Issue 139 of Copper Magazine

Ancient Garrard Turntables: Still Relevant Today? – PS Audio

Ancient Garrard Turntables: Still Relevant Today? Part Two – PS Audio

Written by Adrian Wu

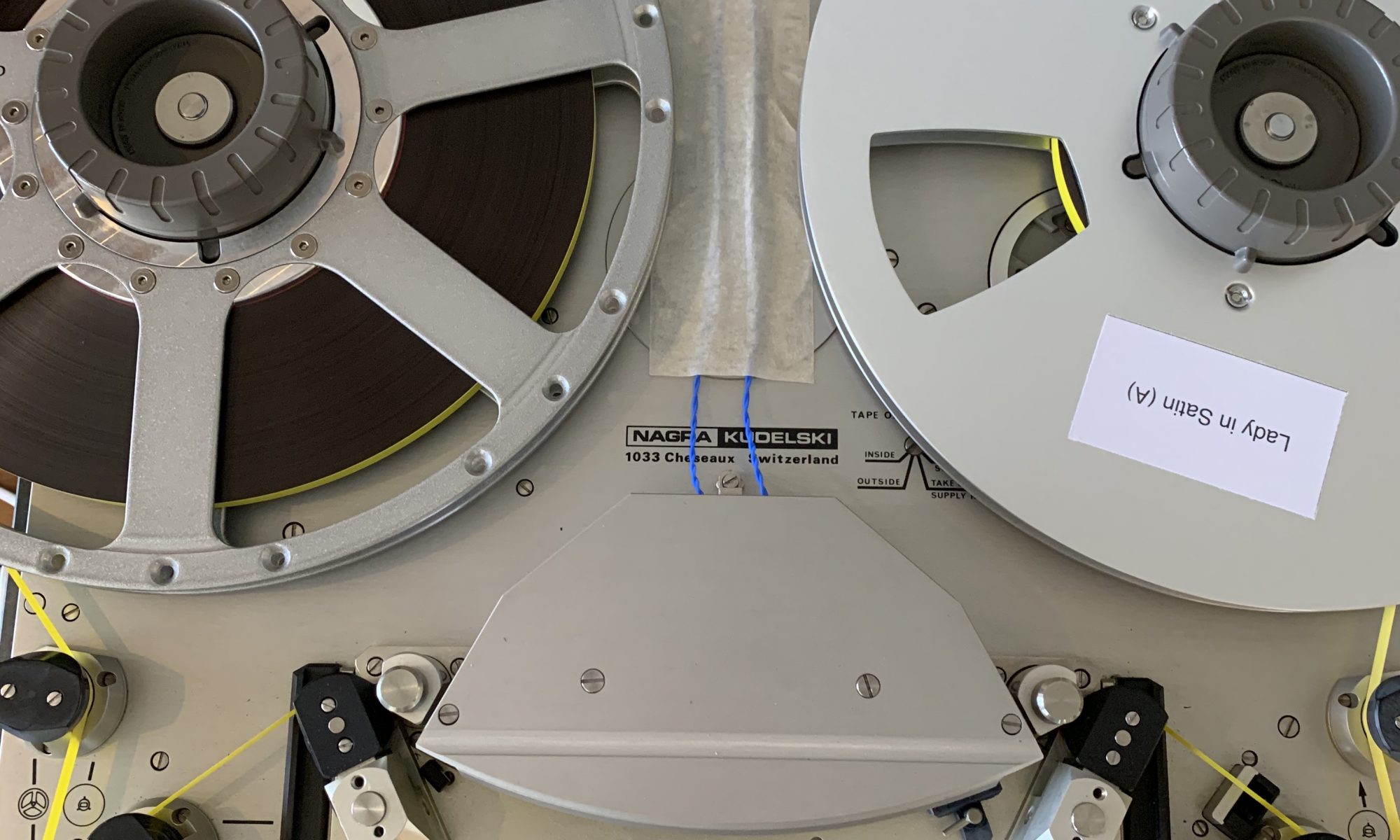

When I first got into this hobby in the early 1980s in the UK, Linn ruled the land of turntables, and British audiophiles hung on to every word uttered by Ivor Tiefenbrun, Linn’s charismatic founder. Tiefenbrun preached the importance of the source component (no consumer digital equipment was available at the time, so that meant the record player, unless you were one of the real geeks listening to open reel tapes), and reputedly once quipped that a Linn Sondek played through a transistor radio would sound better than a lesser turntable (everything else) played through a hi-fi system. At that time, the paradigm for a high-end turntable in the UK meant that it must be belt-driven, with a lightweight suspended subchassis and frictionless main bearing. To prevent transmission of motor noise to the lightweight subchassis, low-torque motors were often used.

Linn did not invent this form factor, but simply borrowed the design of the Ariston RD11 (Ariston contracted out the manufacturing of its turntables to Castle Precision Engineering, Tiefenbrun’s father’s company), which in turn was “inspired” by the Thorens TD150 and the original AR turntable. This type of turntable has a readily identifiable sound, which is rather colored by today’s standard, but in a euphonic sort of way, due to the resonances introduced by the suspended subchassis. During the same period, the Japanese went the other way, with unsuspended turntables on massive plinths, opting to sink the vibrations into the mass rather than to dissipate them with springs or rubber mounts.

Looking back, it is rather amazing how the Garrard transcription turntables, so dominant for almost two decades, had been completely erased from the collective memory of British audiophiles less than a decade after production ended. Ask any young British audiophile in the early 1980s about the Garrards and you would most likely be rewarded with a quizzical stare. Ask any seasoned audiophile and you would invariably hear the word “rumble” mentioned. The only audio rag that wrote about “classic audio” at the time, Hi-Fi World magazine, had a brief entry about the Garrard 301; the only recollection I have from this write up is something about a “veiled treble.”

While these classics were being relegated to the scrap heap in good ol’ Blighty, the Japanese were buying them up hand over fist and shipping containerfuls of them back to Japan, where they were sold at multiples of their original cost. More model 301s (and 401s to a lesser extent) now reside in Asia than in their home country. Were the Japanese just a nostalgic lot, or did they know something that the British audio establishment did not?

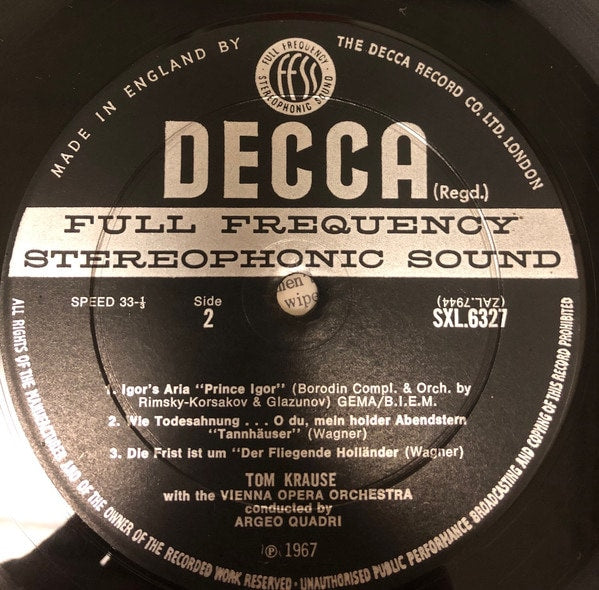

Before the advent of the AR turntable, serious turntables usually had idler wheel drive. The Rek-O-Kut, Thorens TD124, various Lenco models, and the EMT 927 and 930 are other famous examples. The Garrard 301 was introduced in 1953, and the moniker referred to the fact that it could play in three speeds; 78, 45 and 33-1/3 RPM. The 33-1/3 RPM long-playing record had just been introduced. The first units were in a gray hammertone color, and had a main bearing lubricated by grease. The bearing came with a reservoir filled with grease, and a knob, accessible through a hole on the motor plate, can be turned to squeeze more grease into the bearing when necessary. This early version was labeled as “Schedule 1” on the name plate.

When first introduced, the 301 was immediately heralded as a major advancement in turntable design. It was widely adopted by music studios, radio stations and serious audio enthusiasts, with tens of thousands sold. The paint work was changed to a cream color in 1957 to make it look more contemporary and less industrial, and the bearing was “upgraded” to an oil version later that year. The version with oil bearing is labeled as “Schedule 2” on the name plate. The grease bearing model now commands a higher price, probably more to do with rarity than with any performance advantage. I have owned both versions, and I have not noticed any difference. Considering how old these turntables are now, the condition of the bearing probably matters more than the type of lubrication it employs.

In 1964, the 401 was introduced with a completely redesigned chassis. In my opinion, while the look of the 301 is timeless (the Volkswagen Beetle is another example of a timeless design), the 401 looks more at home with bell bottoms, wide lapels and bushy sideburns. The 401 brought some refinements, including better shielding for the motor to reduce hum, a stronger eddy current brake that allows for a wider speed adjustment, and a lamp for viewing the strobe platter. Garrard continued to produce the 301 until 1966, and the 401 was discontinued in 1976, succumbing to the competition from Japanese imports.

When I bought my first turntable, I completely believed in the dogma that turntables should have a belt and suspension. My first turntable was a second-hand Dunlop Systemdek, another Scottish creation and a descendent of the Ariston (Peter Dunlop bought the Ariston company after the latter’s relationship with Castle Precision Engineering ended.). I eventually moved on to the Roksan Xerxes, a design that purportedly addressed the shortcomings of suspended subchassis designs. The main bearing and tonearm are mounted on a lightweight MDF board, which is isolated from the bottom board by rubber mounts. The motor is mounted on the bottom board, suspended by springs. Touraj Moghaddam, Roksan’s founder, claimed that he was inspired to design his own turntable when he noticed that music coming from his television sounded more satisfying than his Linn/Naim high-end system. Talk about turning the table on Ivor! Indeed, my Roksan had more solid, stable imaging and was less colored than the Linn Sondek. Unfortunately, it did not survive the Hong Kong humidity for long and the top board warped, which was the most problematic weakness of this product.

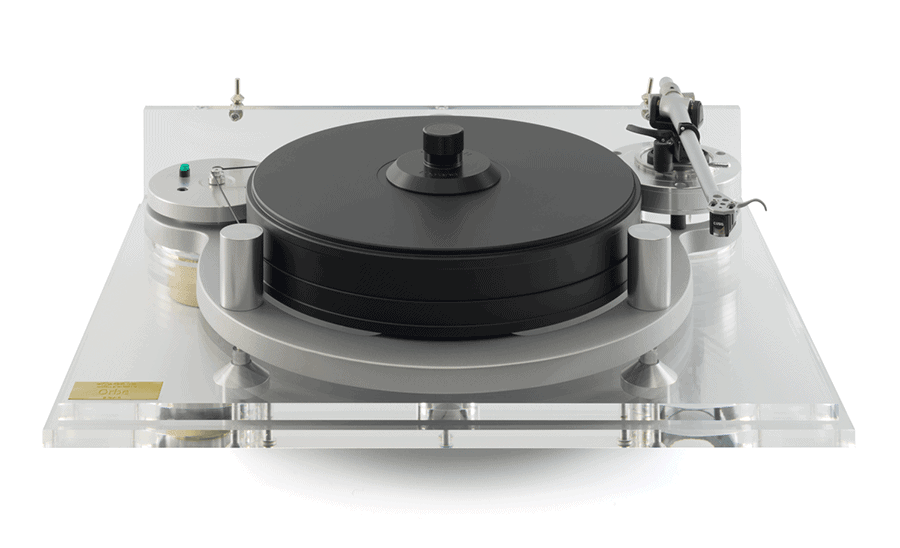

My next turntable was a Michell Orbe, the big brother of the famous Gyrodec. So, back to a three- point suspension system with a belt drive. However, the subchassis in the Orbe is hung from the suspension, and the low center of gravity means much better stability.

I don’t remember exactly where I first laid eyes (ears?) on the Garrard 301. It was probably in a friend’s friend’s system. Although I had heard about the revered status of this turntable in Japan, I was nevertheless quite skeptical, having been biased by all the negative views expressed by the British hi-fi brigade. However, just one audition was enough to clear away all my skepticism. Far from perfect (it was an original, unmodified machine), there was nevertheless a musicality that had been missing from all the other turntables I had heard up until then.

It is difficult to put a finger on that je ne sais quoi, but a piano sounded like a piano (and I knew what a piano should sound like, having struggled with it daily for more than 20 years at that point), which is usually not the case with record players. In fact, piano music was the only genre I preferred to listen to in digital. Everything just sounded more alive and the sound was more palpable, for lack of a better description. So off I went to look for a good clean example for purchase. I just happened to come across one at a hi-fi shop in London. It had been refurbished (clumsily, as it turned out) and was on a slate plinth, a feature I will come back to later. It also came with an SME 3012/II tonearm (the version with a plastic knife edge bearing, sadly).

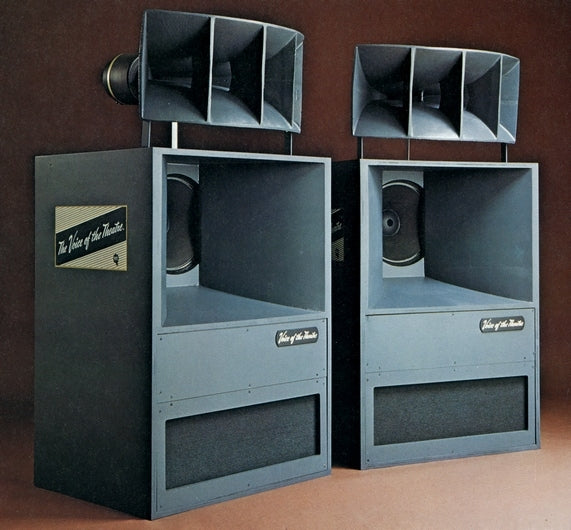

First, how does one reconcile the chorus of criticisms coming from the British audio hacks to the praises sung by the Japanese audiomaniacs? I soon learned that it all comes down to implementation. Both the 301 and the 401 were sold as motor units without plinth. In the 1950s and ’60s, console music systems were common, and many consoles came with cut outs that fitted these motor units. Consumers therefore just bolted the motor unit to the console. Third-party plinths were also available, usually just boxes made from six pieces of plywood with a cutout on one surface. The Garrards have a brute of a motor that makes all other turntable motors look like toys. Many of these decks were used in radio stations and studios, where instant startup was a requirement. A 301 gets up to speed within two to three revolutions, whereas some belt drive turntables with a heavy platter and a weedy motor can take minutes. This powerful motor is the reason for the unit’s outstanding performance, but also a potential cause for its downfall. Even though the motor is suspended by springs, it still transmits a significant amount of vibrational energy to the chassis. Mounting the unit in a hollow box or a console has the same effect as a guitar or a cello with a hollow body; the resonances of the guitar and the cello give the instruments their distinct tonal character, whereas the resonances of the plinth muddy the sound of the record player and introduce rumble. To make matters worse, Garrard recommended users to isolate the chassis with springs, just to add another set of resonances! The Japanese had this figured out a long time ago. One of the earliest products to address this issue was the Shindo plinth, made from layers of solid cherry wood to “tune” the resonances. There are now many other options available, from using heavyweight materials (slate, marble) to constrained layer damping using layers of grain-oriented wood, sometimes interleaved with resin.

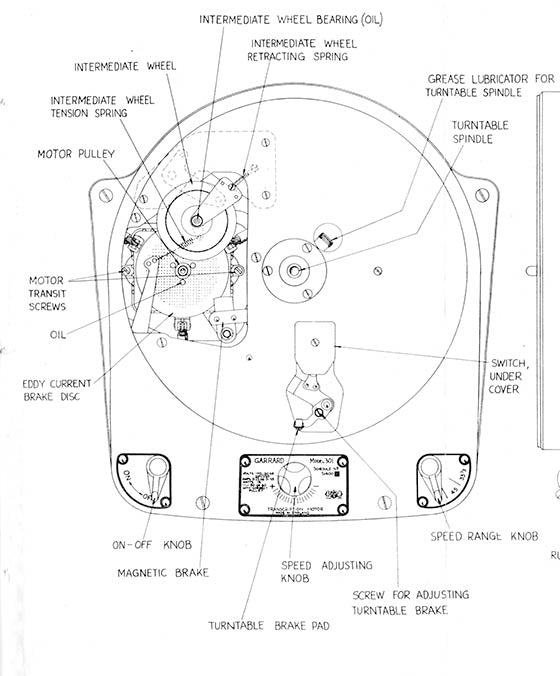

Illustration from the owner’s manual showing the top view of the Garrard 301 motor unit.

The second weakness of the Garrards is the main bearing. While it was state-of-the-art at the time, it was nevertheless a mass-produced part at a time before CNC machining was available. Moreover, most units on the market nowadays have substantial mileage and the bearings are most likely worn. The bearing can be easily removed, taken apart and examined. If it has been allowed to run without sufficient lubrication for a period of time, the housing will likely be worn, and the only remedy is a new housing. The bottom of the shaft directly abuts the thrust pad, which also gets worn out. There are third-party mods on the market that replace the thrust pad and add a hardened steel or ceramic ball bearing. These types of mods often increase bearing noise and bore a concavity on the bottom of the shaft. A loose bearing will result in the “veiled treble” described by the Hi-Fi World reviewer.

The Garrards have an aluminum platter, which was pretty novel at the time. The platter was die cast, which could result in uneven thickness. In order to balance the platter, each one was examined by hand and holes were drilled in strategic locations underneath the outer rim in an attempt to improve the balance. The platter also rings like a bell when tapped. There are several ways to address this. The cheapest is to use rubber rings that fit tightly outside the outer rim to dampen the resonances. Micro Seiki in Japan manufactured a brass (so called gunmetal) mat that also rings when tapped (sounds like a gong), but when placed on top of the platter, the Micro Seiki mat and the platter magically cancel out each other’s resonances. These are no longer manufactured, but Puresound, a company in the UK has started manufacturing something similar, the Tenuto Gunmetal Turntable Mat. Apparently, glass mats can achieve a similar effect, but these would have to be very thick, which could play havoc with the VTA. One also needs to somehow lengthen the spindle.

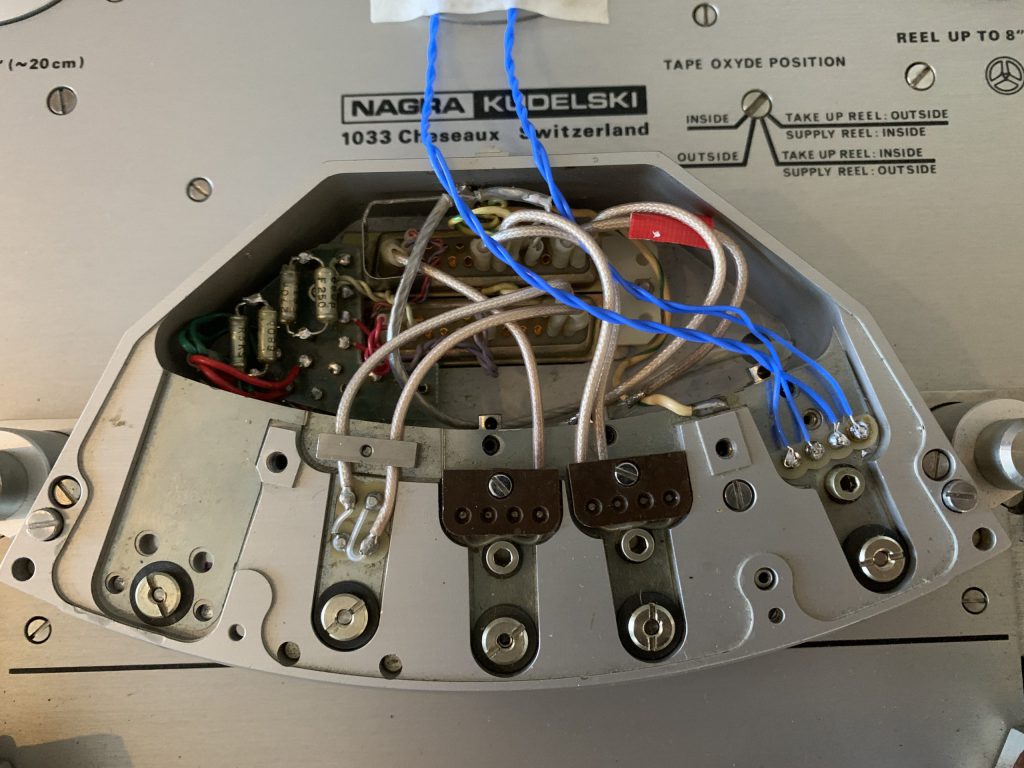

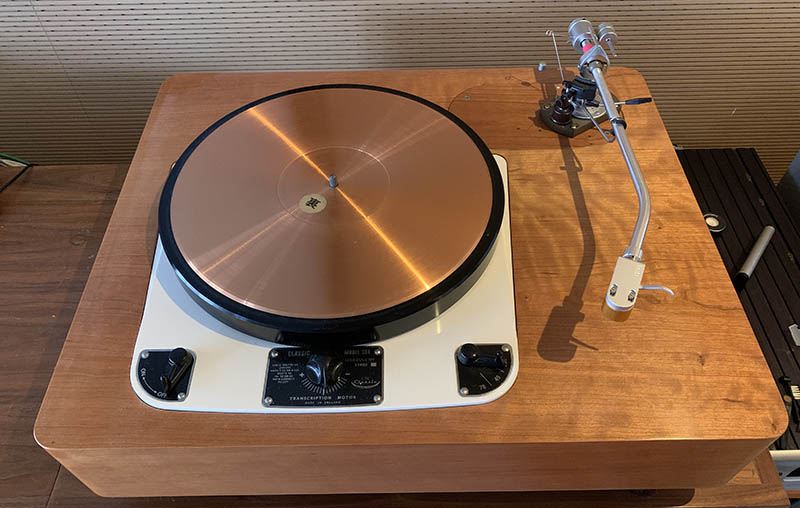

The author’s Classic 301 motor unit with Micro Seiki gunmetal mat.

Another point of contention is the eddy current brake. In the Garrard 301, an alloy disc on the motor shaft sits between two flat metal pole pieces attached to a magnet. The coverage of the disc by the pole pieces can be adjusted to increase or decrease the braking, or even be disengaged altogether. Some people think that the brake exerts unnecessary strain on the motor, which in turn can increase motor noise. However, when disengaged, the platter will run too fast. Therefore, some users opt to reduce the voltage supplied to the motor and lower the frequency of the power supply (using a regenerative power supply such as a PS Audio PowerPlant) to correct the speed. Personally, I think this is a bad idea. Most belt drive turntables have a low-friction bearing. Once the platter has gotten up to speed, the motor is only supplying enough force to overcome the friction of the bearing.

In tracking the record groove, the stylus also produces drag, and this force varies with the linear velocity of the groove (and hence decreases as the stylus tracks across the record) as well as the groove modulation. This means the drag can change suddenly as well as gradually. Imagine towing a truck across a frozen lake using a chain. You are all right as long as you are going at a constant speed or accelerating, but when you try to slow down, the truck will hit you from behind because there is no friction to slow it down. Therefore, the motor of a belt drive turntable has to prevent the platter from slowing down and speeding up by means of the belt. The belt can stretch as well as slip, and this is exacerbated by the length of the belt. The result is smeared transients and wobbly tone, which is especially noticeable with piano music. I discussed this with Tim de Paravicini after I found out that he had implemented sometime akin to the eddy current brake in his turntable (which employs a short, toothed belt between the motor and the sub-platter). He said the motor should always be working against resistance in order to respond to sudden changes in friction. In a typical turntable, when the drag suddenly diminishes (say after a loud chord played on a piano), the motor suddenly loses resistance to work against, and it will accelerate momentarily (even if there is servo control, which needs a finite amount of time to react). Once it corrects itself, it needs to slow down the accelerating platter, which is harder to do since the motor is supposed to apply force in one direction only via the belt (like trying to slow down the truck via the tow chain).

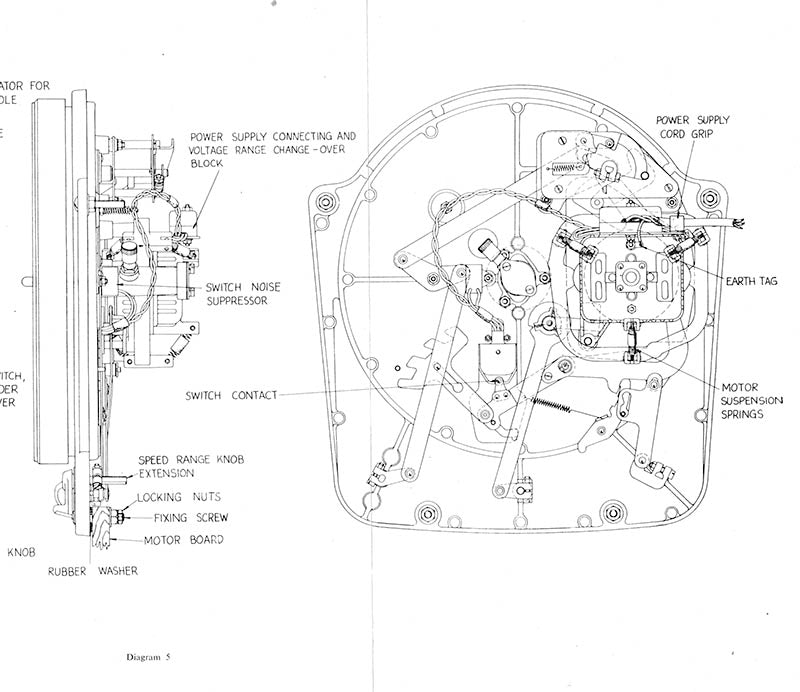

Illustration from the owner’s manual showing the side and bottom views of the Garrard 301 motor unit.

There are ways to ameliorate this problem, such as using heavy platters, flywheels, multiple motors etc., but each solution brings its own set of problems. In the Garrard, the motor is coupled to the rim of the platter via an idler wheel. Unlike a belt, there is no stretching and minimal slippage, and the tight coupling makes it easier to slow down as well as speed up the platter. The eddy current brake applies a constant opposing force on the motor, which is orders of magnitude greater than the stylus drag. Any sudden change in stylus drag therefore only represents a small percentage of the overall resistance, and its importance is greatly attenuated. This accounts for the superior transient response and tonal stability of this turntable.

The idler wheel system can also be a source of trouble. The coupling of the idler to the motor pulley and the platter is regulated by springs. With age, the spring tension diminishes and speed stability suffers. The rubber rim of the idler wheel also hardens with age, losing grip and increasing the transmission of vibrations. If the idler wheel is left engaged with the power turned off, a flat spot on the rubber rim will develop, which will lead to speed fluctuations. Therefore, the turntable must always be turned off at the switch, not simply by cutting off power.

In Part Two, we will look at modern upgrades for Garrard turntables, and the SME re-issue of the legendary model 301.

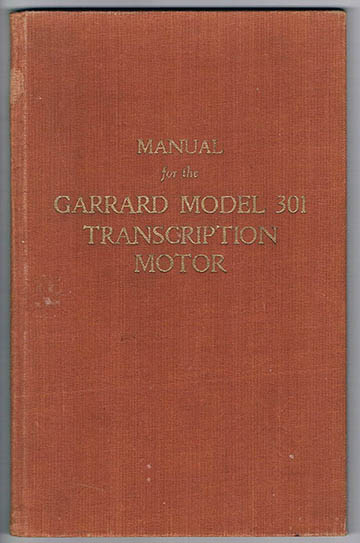

Garrard owner’s manual: the hard back and gold lettering meant business!

Header image: Garrard 301 turntable ad, 1958.

In Part One (Issue 139), Adrian Wu outlined a history of Garrard 301, 401 and other turntables, and provided an in-depth examination of their advantages and foibles. Part Two concludes with a look at some modern upgrades, and the SME re-issue of the legendary model 301.

The Garrard company was founded in 1735 as a jewelry maker, and it remains a high-end jeweler by appointment to the Queen to this day. The company founded a subsidiary, Garrard Engineering and Manufacturing Company, in 1915 to produce motors as part of the War effort. After World War I ended, it needed to reinvent its business and entered the nascent gramophone manufacturing sector. Decades later, after losing market share to Japanese competitors, the parent company sold the business to a Brazilian investor in 1979, who ended its business activities. Loricraft, an English company specializing in record cleaning machines, licensed the Garrard name in the 1990s and provided servicing for the Garrard turntables. They also re-manufactured many parts, designed new plinths, and eventually produced a Garrard 501 turntable of their own design. This turntable was regarded as an oddity at a time when belt drive ruled the roost, and the mainstream British audio press never took much interest in it.

In Japan, Ken Shindo had been working on the 301 since the 1960s and had come up with a new main bearing, idler and platter. Together with his plinth, a 12-inch tonearm modeled after the classic Ortofon RF-297 and a highly modified SPU cartridge, the record player was sold as a complete package. This record player was and still is taken very seriously indeed by the Japanese audio community. Loricraft and Shindo remained the only game in town, if you didn’t want to get your hands dirty and work on refurbishing turntables yourself, until the early 2000s. With a revival of interest in these classic turntables outside Japan, many companies have sprung up in the last 15 years to provide servicing and modifications as well as plinths.

Slate Audio (now defunct) was one of the early players, and they claimed slate has a natural structure well suited to damping the vibrations of the Garrard motor. The first 301 I bought had a new paint job and zinc plating of the links that operate the idler wheel mechanism (the originals were plated in cadmium, a toxic metal), but everything else was original. The color of the paint did not quite match the original, and the zinc plating started to peel off after a while. I also discovered that the power cable to the motor was not rewired in a safe fashion. The slate plinth had a faux marble outer finish that looked good enough, but the finish of the edges was rather rough. Nevertheless, it was cheap, at 1,000 pounds (in 2003) for the whole lot including tonearm and a slightly used Clearaudio cartridge. It had some wow until I bought a new idler wheel and a set of springs from Loricraft, which fixed the problem.

After a couple of years, I came across a cream-colored grease bearing unit, which I bought to replace the oil bearing unit while keeping the same plinth. There was not a lot of difference sonically between the two units, but I believed the design was capable of a whole lot more. The sound was lively, impactful, with solid imaging, but the pitch was still not as stable as it should be, and the frequency extension could have been better.

I then came across a new main bearing that was receiving a lot of rave reviews on the bulletin boards. The company was called Red Beard Audio, and it was basically a one man operation. The guy owned a machine shop and produced every bearing himself by hand. It has an oversized shaft and housing with very tight tolerances, and does not rely on bushes, ball bearings or thrust pads. It uses a highly viscous synthetic lubricant that has a consistency between oil and grease. It was a major improvement over the original bearing, with vastly improved frequency extension and a tighter impact. He was very successful initially by all accounts, with a large backlog of orders. Sadly, he had some quality control issues once he started to scale up production, and some unhappy customers demanded replacements, which he was not able to fulfill in a timely manner. Some of these irate customers became very vocal online, which led to the collapse of his business. Being an early customer, I have had no issue with the part, which is still working perfectly with no sign of wear after more than a decade.

During this time, I also upgraded the knife-edge bearing of the SME 3012/II tonearm and rewired it. With the new main bearing, the turntable has finally reached a satisfactory level of musicality. However, I was still in constant search for perfection, and two obvious areas for improvement were the plinth and the chassis.

People argue endlessly about the overall merit of a slate or marble plinth versus a wooden plinth with constrained layer damping. The former aims to sink the vibrations into the mass, whereas the latter is supposed to spread the energy over a wide range of frequencies. Advocates of wooden plinths claim the slate deadens the sound, whereas the other camp claims that the “tuned” plinths color the sound. As for the chassis, the original 301 chassis was made of cast aluminum. It is only supported around the edge where it sits on the plinth, and it is possible to flex the center of the chassis if one pushes down on the bearing. This lack of rigidity means vibrations from the bearing gets reflected back to the platter, record and stylus. The 401 chassis addressed this issue with bracing underneath to make it more rigid, but the 301 chassis looks way cooler.

I found a company in the UK called Classic Turntable Company that machines new 301 chassis out of blocks of aluminum twice as thick as the original. Every detail of the appearance is the same except for the four bolt holes. Instead of inserting the bolts through the chassis, the bolts are screwed into the bottom of the chassis like the 401. The company also produces platters with perfect balance, made from machined aluminum or brass, as well as an improved idler wheel and main bearing. I therefore packed up my motor unit and shipped it to them. They stripped and rebuilt the motor, stripped and chrome plated the links, replaced the springs, idler, spark suppressor and chassis, and replaced all the wiring. I also bought a new aluminum platter. I did not replace the bearing, as the Red Beard remained in perfect working order.

In essence, I got a new turntable unit except for the bearing, links and motor. The company also recommended a cabinetmaker who had been making plinths for their customers for many years. I bought a solid cherry wood plinth with a natural finish. This new round of upgrades cost around 2,500 pounds, a bargain in high-end terms.

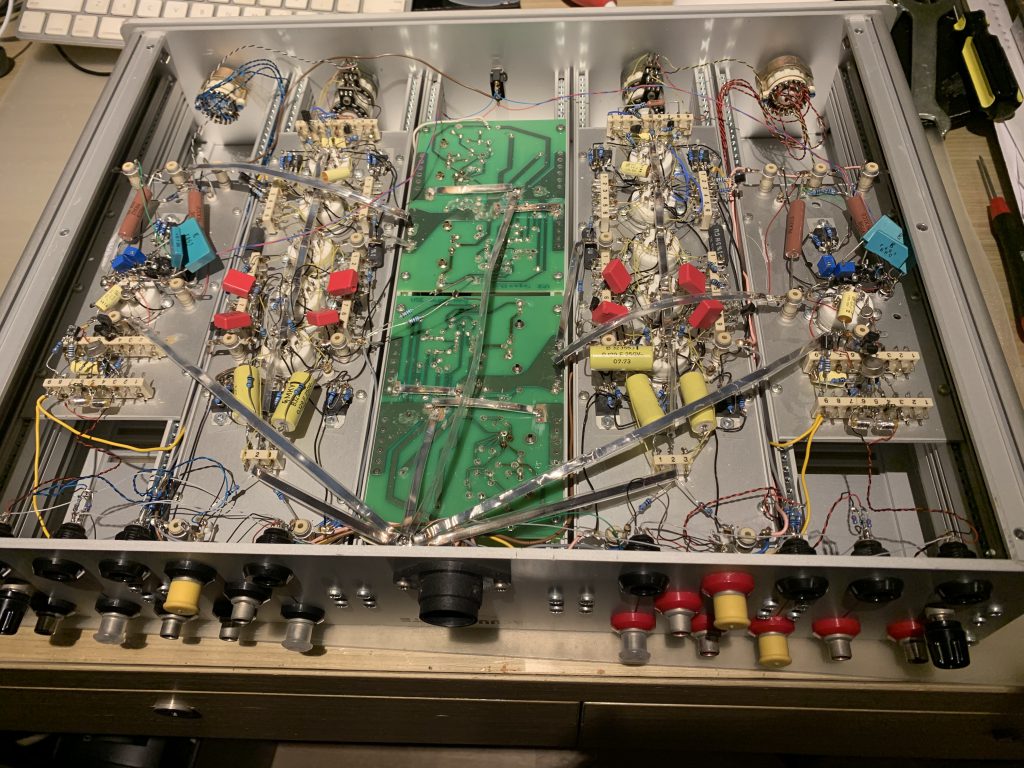

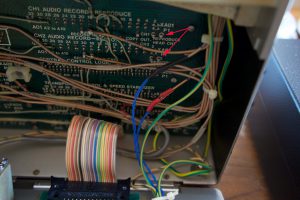

The whole thing came together nicely and the record player has ascended to the next level of excellence. With well-mastered LPs, the performance approaches that of tapes played on the Nagra T Audio open reel deck. I can still identify some deficiencies, such as a slightly emphasized mid-bass, but I suspect this might be due to the tonearm. The tapes still have a bit more of that eerie see-through quality, and the soundstage is wider and deeper still. However, this record player is now competitive with some serious high-end turntables.

Adrian Wu’s completed Garrard 301 with solid cherry wood plinth, Tenuto gunmetal turntable mat, modified SME 3012 Series II tonearm and Ikeda 9TT cartridge.

In 2018, SME announced that they had bought the Garrard trademark, as well as the Loricraft company. The following year, they showed a “new” original 301 built with New Old Stock (NOS) as well as remanufactured components. The plinth follows the Loricraft design, which has a top plate supported by four rubber mounts, similar to the Roksan. The machine is only sold with a 12-inch tonearm, a descendent of the 3012. I have not seen an official price yet, but have heard various estimates from £12.5K to £20K.

[Note: as of press time, there is a website with an official-looking web address for Garrard, but when attempting to log on, a warning message comes up that the connection is not private and the site may be trying to steal information. No information about the new turntable is available on the SME website. We will attempt to find out more. – Ed.]

While I am happy that these classic machines have again re-entered the mainstream consciousness, I cannot help but wonder if SME got it wrong. Re-creating the machine exactly as it was might appeal to vintage audio enthusiasts, and there is certainly a market for that, but most audiophiles are interested in this design for its potential to achieve state-of-the-art performance using modern manufacturing technology. That is why so many people have worked on improving the parts. SME, being a top precision engineering company, should be perfectly placed to make significant advancements. Will serious audiophiles pay £12.5K for something manufactured with 1950s technology? Of note, Thorens went so far as to “update” their classic TD124 with direct drive. I feel this might be going a bit too far, since the idler wheel drive of that machine is the soul of the design. They should perhaps offer two choices, idler wheel or direct drive. The proof of the pudding is in the eating, and I look forward to the chance to audition the “new” 301 in its original glory, and would love to be proven wrong.

Here are links to a few other vintage Garrard restoration specialists and parts companies:

Layers of Beauty: a specialist antique furniture restorer, cabinet maker and plinth maker for vintage turntables.

Artisan Fidelity: this US-based company is a restorer of vintage turntables and plinths, offers upgraded parts, and is also a retailer for a number of high-end brands.

Perfect Sound: the largest spare parts manufacturer for Garrard turntables, and an authorized Loricraft parts supplier.

Woodsong Audio: the company offers Garrard, Thorens and Linn Sondek LP12 restoration, plinths and parts, as well as a variety of cartridges, tonearms and other products.

TJN Analog/ Turntables by Jean Nantais: he restores Garrard, Lenco and other turntables.